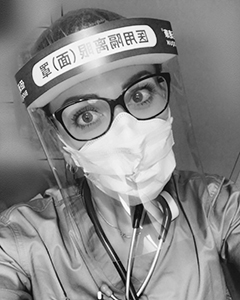

In this issue, we talked to Dr. Julia Iafrate of Columbia University's Department of Rehabilitation and Regenerative Medicine in New York, NY. Dr. Iafrate works in sports medicine and volunteered her expertise in PM&R to the frontlines at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The following article is based on her experience as of late July 2020.

Julia Iafrate, DO, CAQSM, FAAPMR

Julia Iafrate, DO, CAQSM, FAAPMR

Director of Dance Medicine

Assistant Professor

Department of Rehabilitation and Regenerative Medicine

Columbia University Irving Medical Center

In a year wrought with conflict on every level, I made a decision - I preferred it to be me. I preferred it to be me that went to the frontlines instead of one of my colleagues who had kids or who was older and farther removed from residency. I chose myself to go to the frontlines.

Back in early March 2020, we were still seeing patients in our NYC outpatient clinic, but as the coronavirus spread and New York became a hotspot, everything transitioned rapidly. Initially, as most places did, we all transitioned to telehealth and were only seeing emergencies or urgent procedures in clinic, but within the first week, we noticed how fast our numbers were climbing. My department (the Department of Rehabilitation and Regenerative Medicine at Columbia) got redeployed over to Workforce Health and Safety; providing care to hospital workers who would call and say, "I think I have symptoms of COVID-19, what do I do?" Soon enough, we started having so many healthcare workers with symptoms of COVID-19 that we didn't have enough people working anymore. We still didn't have enough tests to evaluate everyone.

Fast forward a few weeks later when an email went out reporting we were running out of doctors and hospital workers. That was the point when I volunteered to go to the frontlines. In fact, I was chomping at the bit to go there - to be a person, be a body and help out. This is such an interesting time of our lives as doctors and healthcare workers. A pandemic? Honestly, it is something we probably won't ever see in our lifetimes again, and so being part of that is kind of a big deal. And having faith in our medical training, in our abilities, is so important. We should never think, "Oh, I only focus on PM&R and I don't take care of these other medical issues." Yes, you do. Yes, you can. Yes, you have. This is real medicine.

I won't lie, my friends thought I was nuts to move to the frontlines. But none of this was out of character for me. I've done a lot of international medical trips, in which I'm usually practicing outside of my typical scope of practice. I'm that person that runs toward the fire; I run toward the danger. I felt a deep-seated need to help. That's why I got into medicine in the first place.

So, while everyone else was socially isolated at home, cultivating a newfound love of puzzles and online wine parties, I faced the frontlines. I started in the ER for about two weeks; working in a makeshift ICU because we didn't have enough beds in our MICU and SICU for all the patients. Eventually, the ER was overflowing too, so we transitioned a number of our operating rooms into OR ICUs.

For the first month and a half, it was terrible. Non-stop every day, 13-hour days. Some patients were making it, most people weren't and a lot of people were on ventilators for days on end, leaving me with a sense of extraordinary sorrow. I went into PM&R because I love talking to my patients. I love making them functional. And here I was, in a mini-ICU, all my patients on vents, just hoping to help them get through the day. I wanted to cry because it was so terrible. I am so grateful that through it all I still had my personal community at home to help get me groceries, or participate in Zoom dance parties or boxing lessons. This helped keep me as mentally healthy as possible, but I was still struggling. It didn't help that I was battling to get my green card at the same time. Facing COVID and deportation in the same year? Not my favorite.

This experience really allowed me to get out of my sports medicine bubble. In my practice, I interact with orthopedics, neurosurgery, neurology, and primary care. That's about it. Yet, now I have colleagues that I actually know in the ER and the critical care unit; people that I know in anesthesia that I wouldn't have met otherwise. Having had this experience makes you proud to be in medicine and gives you an appreciation for each other's specialties. And that goes both ways.

When I first started in the ER ICU, my medical colleagues were so happy to learn I had these ultrasound skills and was able to efficiently drop arterial lines into all our patients. This helped nursing spend less time in each room drawing blood and allowed us to track vitals more easily. During one of my later shifts, we had a patient develop a pneumothorax, and I was able to do a needle decompression with the surgical resident - something I learned from field trauma training during my sports medicine fellowship. They were like, "well, s---, who knew PM&R could do that?" Getting them to realize what physiatry could do was really cool.

PM&R has been essential because we are always considering what comes next, and I don't think a lot of other specialties think about that. We know a lot of other physicians diagnose and treat, but once you're "fixed", they say, "I've kept you alive, I did my job" and send you on your way. But those of us in PM&R have this mindset of looking forward and saying, "Okay, here and now is great, but where does this path lead? What's through that door over there? And if I can't get through that door, how do I open a window to get through instead?"

I like to think of us as detectives and our patients like puzzles, almost, and you have to piece them back together because they're broken to some extent. Having the ability to think through all of those different behavioral aspects - cognitive aspects, motor aspects, pulmonary problems, cardiac issues, risk of thrombolic complications, etc. - is what I believe PM&R does better than other specialties. Physiatry thinks globally because we consider how all those issues apply to a patient's function, how to get them back into society and how we make them feel "normal" again.

I call this the second phase of COVID management (the first phase is done: we kept you alive, go team!) and it's where PM&R shines. Without this specialty, without the mindset and the teamwork that happens within PM&R (working with rehab therapists or psychology or neurocog specialists, other physicians), without that combined effort, people would fall through the cracks.

Eventually, we were able to shut down our OR ICUs and get our numbers back down. Things started to normalize slightly in New York. I was able to go back to sports medicine and PM&R. Telehealth continued, but at the same time we were also building a COVID-19 inpatient rehab unit. Just because you don't die doesn't mean you automatically go back to normal. There were so many patients that were finally coming off ventilators after 20, 30, 40 days who were so debilitated by then, who so desperately needed PM&R and the care that we provide, that there was no way they were going to be able to go home without it. We know this in our specialty. It was really amazing to see how well our department bonded together and said, "Okay, I'll do whatever I have to do. Let's figure this out, let's contribute and do what we can."

From an inpatient perspective, they're going to have to follow these post-COVID patients for a very long time, and I think we're going to see a lot of complications of COVID-19 down the road. I predict our hospital is going to be busy with a post-COVID syndrome that's going to creep up in multiple different ways.

In terms of the sports medicine side of PM&R, a lot of people during the quarantine - even the ones that didn't get COVID-19 - did one of two things: they either didn't exercise very much and/or they ate really poorly. Which means we're going to see a lot more obesity and problems with body image issues and stress injuries. Subsequently, too, once these people are allowed to go back to the gyms they are going to start getting injured because they haven't been training during this time, which is where we're going to see stress fractures that wouldn't otherwise be there and more sports injuries, too. Our patients are expecting to function at the same level they were functioning back in February or March (2020), and that's not feasible.

Finally, I think we're going to see a lot of depression manifesting as musculoskeletal pain. Mental health is going to be important, and I think a lot of the healthcare heroes that volunteered on the frontlines are going to have issues with mental health. I wouldn't be surprised if some of them start having chronic fatigue syndromes, myofascial disorders that stem from depression or from an outside source of pain that manifests within the body.

We're going to see things that we've never seen before and we're going to need to figure out how to work around them and how to get people feeling better. We need to utilize central locations like the Care in the Time of COVID-19 forum on PhyzForum that we can all pour our findings into, to discuss these cases that we've had to try to help each other out. Additionally, we need more research and more expert opinion pieces, people that have experience with this. What are you seeing? What do you think would be helpful?

I want to see more sharing amongst ourselves and our other medical colleagues. We should all be thinking that way, even though a lot of physiatrists don't necessarily gravitate toward research because we're such "people-persons." But I think that this is one of those times when case reports are going to be hugely helpful - those little odd situations that you thought outside the box and had a successful outcome. Well, maybe somebody else might want to try that and look into it. And the exposure helps us spread the word. The exposure helps us figure out how to manage these new diagnoses.

I believe that is what's going to bring PM&R to the forefront. PM&R is still a lesser-known medical specialty. If we can do good work here, I think it's only going to benefit our specialty as a whole. A lot of med students are going to be stimulated by that thinking outside the box, "the MacGyvering", the puzzle master kind of mindset. We have a very awesome perspective because we see our patients' health from a bird's eye view; like we're seeing the whole playing field. We use that kind of knowledge and that interest to impact the long-term storyline of their lives to try to figure out how to create a better existence for them. It's beautiful.